Week 39: #52 Ancestors – Map It Out

By Eilene Lyon

Note: This three-part series is adapted from my California gold rush book. Sources will be listed at the end of Part 3.

Background

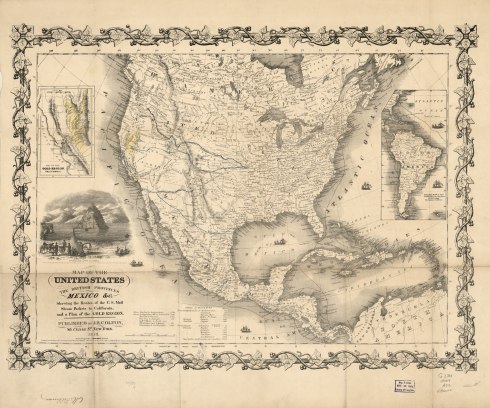

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848 set off the largest mass migration to a single destination up to that time. In the decade to follow, some 300 thousand people would converge on Alta California, hoping to make their fortune.

The earliest Argonauts embarked in New York City and sailed “around the Horn” (the tip of South America), a harrowing voyage that could take six to eight months. Tens of thousands gathered in western Missouri in early spring 1849 to make the overland journey on the Oregon Trail. Some people, particularly from the south, took the old Spanish Trail in what is now New Mexico and Arizona.

Soon, the seafaring crowd began taking a shortcut across the isthmus from Chagres to Panama City, or by trekking across Mexico from Vera Cruz to one of the Pacific ports: Acapulco, San Blas, or Mazatlan. There, they hoped to find a ship bound for San Francisco.

It took some time for the steamship companies to provide regular packet ships to ply the route between Panama and San Francisco, but by the early 1850s, that was the most practical route.

My ancestors from Indiana chose an unconventional way to get to California. Rather than traveling to New York to board a steamship, they went to the Ohio River and took a steamboat to New Orleans.

Indiana Gold Miners

The ten men making up the Blackford Mining Company, including my relations Henry Zane Jenkins, John and Humphrey Anderson, and Sam Jones, departed Trenton, Indiana, on March 10, 1851. The steamboat trip from Cincinnati to New Orleans took ten days, the first part unpleasantly cold as they huddled on the open main deck among the freight.

Due to the illness and death of Humphrey in New Orleans, they missed their chance to take a steamship to Chagres and had a miserably slow journey on the brig Josephine, instead. In Panama, they were able to obtain steamship passage, though at a premium price.

The average steamer took about 21 days to get to San Francisco. The Blackford group arrived at their destination on May 24, 1851 and immediately headed to the mines in Calaveras County. The entire trip took them two and half months and cost about $250 each.

William Ransom, Henry Jenkins’s son-in-law, had planned to be part of that company, but for some unknown reason had been left behind. He wasn’t the only one in Blackford County wanting to get to gold country. By early 1852 another 20 young men from the area banded together to make the trip. They also took the river route to New Orleans.

The men left home in early or mid-February 1852, traveling together, but not as a company. Each had barely enough funds to get them to the west coast. In fact, Henry’s son, Will Jenkins, realized the shortage and turned around in New Orleans and went home.

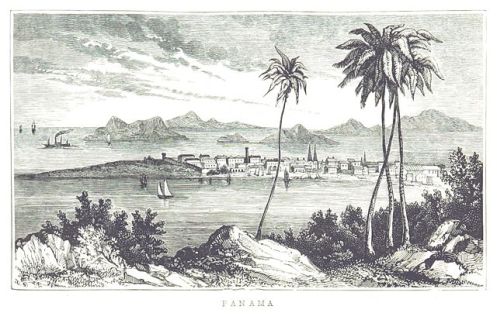

The others boarded a steamship in the Crescent City to Havana, where they switched ships for one heading to Aspinwall (aka Colón), the new port that had replaced Chagres. All was well until they reached Panama City and they discovered the disadvantage of their unconventional route.

Passengers from New York had “through tickets.” These tickets not only covered their passage to Aspinwall, but also the journey across the isthmus and passage on the Pacific side. The holders of these tickets booked all the Pacific fleet of steamships full for months in advance.

The Old Sailing Ships

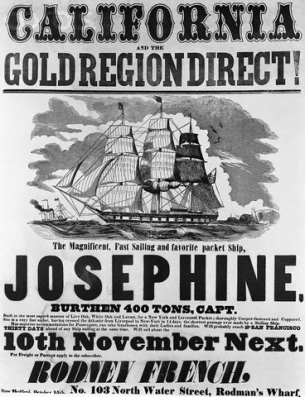

All around the world, the demand for passage to California quickly depleted the active fleets. Soon, any old hulk that could float (and some that couldn’t) began hauling eager wanna-be miners across the oceans. Enter the old sailing ships.

The captains of these vessels were not always versed in the best way to get to California. Their charts and knowledge of the winds and currents could be devastatingly deficient. Still, their agents usually found desperate men willing to pay good money for the trip – men who soon regretted ever setting foot aboard the vermin-ridden, ill-supplied ships.

One of these ships was a British barque named Emily, which sailed from London, to Sydney, Australia, then to Panama. The large ship was loaded with 500 tons of Sydney coal. Capt. Harvey had likely never sailed to California. Experienced captains knew to sail to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), and from there to California – a journey that could be made in 40 to 60 days in favorable weather.

Most of the second Indiana group purchased tickets for the Emily, not even having laid eyes on her; ships arriving in Panama City had to anchor several miles from shore. The Emily’s voyage became notorious, from San Francisco to the Royal Geographic Society in London. One of the passengers was my great-great grandfather, Robert Ransom.

Use this interactive map to view the legs of the journey that Robert Ransom took to California in 1852. You can zoom in to various sections and click on points and lines for more information.

Panama

The group from Indiana, most from Blackford County, included Robert Ransom and his older brother, William; the Ransom’s neighbors, Henry and Jackson Cortright, plus Hazelette Lanning; friends Samuel and John Leaird, of Delaware County; Frank Taughinbaugh, son of the Blackford County clerk; and John Jackson Twibell. Most were in their twenties.

Arriving in the city, they were dismayed to find there were no tickets for a steam passage to San Francisco. For those with little means at their disposal, the expense of waiting for months in Panama was much too great. These circumstances gave sailing ships an opportunity to capture part of the market.

Agents hawked tickets to the poor and desperate, but the fares they charged were exorbitant, considering the uncertain nature of the trip’s duration and general decrepitude of the ships. In late February an agent was selling tickets for the Emily at $150 each. “She was advertised to go through in 35 or 40 day[s],” according to passenger George Blanchard, one of the more than 200 men who succumbed to the wily agent’s ridiculous claim.

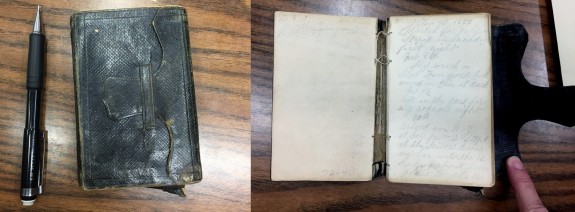

Soon, the passengers who had been charged this outrageous sum realized they’d been ripped off. “Great excitement concerning the independent tickets they have attached the agents purs & intend to make a dividend among the passengers having such tickets,” related David Gillis, an Ohio man who kept a diary on the voyage of the Emily.

The Ransoms were among those who had secured their passage on this ship, along with most of their Indiana companions. William Ransom wrote a letter to his wife, Ann (Jenkins), letting the Ransoms, Jenkinses, and others know their plans. As they prepared to board ship, they were unaware that Captain Harvey had never been to California and knew nothing about the proper route to take.

All Aboard

After the fracas over inflated ticket prices, the Panama passengers boarded the Emily on March 7, 1852 undoubtedly with some trepidation and second thoughts. The local launches carried them out three miles in the bay to meet their floating home. That was when they discovered that “The Barque was not what she was advertised to be She was old and had 500 tons of coal on bord.”

The Emily carried roughly 300 passengers and crew. Some on board were already showing signs of serious illness, particularly a group from Georgia. “About one half of the pasingers were sick soon after we started The principal diseases were the pannama feafor and the Measles all of whitch I escaped & a good many died by not having proper care taking of them,” said Blanchard.

The passengers expected the 3,600-mile trip to San Francisco to take no more than 40 days. The crew of the Emily drastically under-supplied her food and water needs for the long trip and heavy load of people and coal. Capt. Harvey, who appears to have been generally liked by those aboard, attempted to sail north along the steamship route, fighting the winds (or lack thereof) and currents.

For Gillis, a 32-year-old farmer, the trip was an opportunity to document the adventures of his small company of six, as they headed to the mines. He recorded what he felt were the most significant events each day of Emily’s journey, beginning in Panama. His observations reveal just how horrid, and deadly, the trip could be.

[Updated August 16, 2021]

To Be Continued…

Feature image: The British barque Mary Ann Johnston off Liverpool – Attributed to Joseph Heard, c. 1848 (Wikimedia Commons)

They could’ve walked it in less time, but, finding gold often meant losing your good cents [sic] Very interesting. Looking forward to the other two.

LikeLiked by 2 people

An event like that brings out the scammers, big time. These farmers were easy marks, unfortunately.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sure, and as I’ve learned first hand, those super friendlies that meet you all helpful are the ones to watch out for!

LikeLiked by 2 people

You got that right!

LikeLike

Fascinating and well told. Can’t wait for the next installments.

Those old sailing routes were interesting. For instance, the route from England to Australia, stopped in Brazil.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Greg. Part 2 on Tuesday and Part 3 on Saturday. Stay tuned!

I love the old sailing ships, but the reality of traveling on them – not so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Funny how the hills are always mentioned when speaking of the gold rush, but never much talk about the sea. WHAT an ordeal to get there!

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Hills” is such an understatement! But it’s true that most of the well-known gold rush tales involve the overland route.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Right! And yet, to think this was a global phenomenon. And all those journeyers who never even made it to their destination. Gives you perspective.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s estimated that one in ten died on the journey or soon after reaching California. That may also include the ones who died trying to get back home.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Whoa. Perspective indeed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Quite the journey. I wonder at which point they wished they’d never begun it, or was the pull of the gold enough for them to never doubt their journey. Looking forward to reading the next installment!

LikeLiked by 2 people

It astonishes me to read the journals and letters, because they seem somewhat stoic about it all. It’s also true that they didn’t want to alarm their families, so they understated a lot of the hardships, illnesses and deaths.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I can imagine they would have played it cool!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read this account with a great deal of interest. I’d never actually considered Gold Rush Fever from the perspective of individual people and families. I assume “Panama fever” was malaria? I look forward to the next installment!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Panama fever was more likely yellow fever. It wasn’t endemic to Panama, but had been introduced by immigrants over the years. Malaria was generally known as such.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also look forward to the next installments. Fascinating stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To think what they went through… and I get into a tizzy if I might miss a flight.😮

LikeLiked by 1 person

Travel back then was not easy, but I don’t think I realized how many ways a person could get taken advantage of while traveling. It was not for the faint of heart, was it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly not! But there was also something of the young daredevil attitude in many of these men. And though mortality could be high on the road, it was high at home, too. For example, 1849 saw major cholera outbreaks all through the Mississippi valley states.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What horrific experiences! I’m glad to live in the 21st century.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And the tale has just begun…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d love to take a steamboat to New Orleans.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We went on one from Memphis a couple years ago (research, you understand). Unfortunately we caught a bad weather window. But I enjoyed it anyway.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I was less than four we went on a Mississippi River cruise that I have never forgotten. It was so much fun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I’d like to do the Mississippi in a small boat and stop at a lot of places.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too. I was kind of looking at the American Cruise Lines cruises. We did one for Alaska and it was wonderful, but they are really pricey, so I don’t know. Alaska was meant to be a once in a lifetime thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I think they are way too expensive. We got discounted tickets, but still…. That’s why I’d like to just rent or charter a small boat and supply my own food and stuff. I don’t need anything fancy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Our problem is the gardener’s celiac. We have to plan everything out so we know the big boy can get fed regularly and safely. But I am formulating a bucket list. That’s part of my death preparation haha.

LikeLiked by 1 person