Week 43: #52 Ancestors – Transportation

By Eilene Lyon

Stranded

Robert and William Ransom had meager funds. There was no way for them to send a message to their family at home, or to Henry Jenkins in California, to let them know of their predicament. Families in Indiana and elsewhere were sure by mid-summer that the Emily passengers had perished. At San Blas, the men had to live by their wits.

The town was hardly a suitable encampment. The port was small, surrounded by mangrove swamps, and home to innumerable disease-carrying mosquitoes. There was, however, a plentiful supply of fresh water, gratefully consumed by the stranded travelers.

Because the Emily was still in poor condition to accommodate passengers, the Ransoms and their companions had no choice but to await the arrival of alternate transportation to San Francisco. Their trip was certainly not going according to plan.

“The Captain said that he had not money enough for provisions for only 30 days but the counsel said that his vessel was no sailor and he must put on bord 60 days provisions,” said Blanchard. The port authorities refused to let the Emily depart.

While the men were stranded in the village, Capt. Harvey gave them a daily allowance for food of just 25 cents. But the famished men needed four times that amount to get the nutrition they desperately craved. Soon the debt to the locals amounted to $2,000.

The humidity was nearly unbearable by late June, and the seasonal monsoon rains began to inundate the region. Given the dire situation, the marooned men chose two representatives, pooled some funds, and sent them 60 miles to Tepic to visit the U. S. consul there.

The U. S. Consul

William Forbes, who had lived in Mexico since at least the 1820s, was a partner in the British trading house Barron, Forbes & Co. The company was the dominant foreign business on Mexico’s west coast, with headquarters in San Blas. Forbes wisely lived inland, far from the swampy, unhealthy shore.

Though he wasn’t American, he had taken the consulate position in 1850 upon the departure of G. W. P. Bissell, the previous consul.

Forbes and his partners ran a highly successful enterprise that included smuggling as a matter of course. Silver from Mexican mines was their most significant export. They also had a cotton-fabric mill and sold the rough goods at a much higher price than superior imported goods would have sold for – a monopoly achieved through bribes to the Mexican government. Forbes was rich, though his operation involved a great deal of risk to his wealth.

“Mr Forbes is the great man of Tepic – his house is the point of re-union; – every one drops in to tell the news or to hear it. From morning till night there is a crowd of idlers under the arcade, smoking & prosing.” The little committee from the Emily had no trouble locating the consul.

“His house, like most Mexican & Spanish houses, is built round a court or patio, into which all the rooms on the ground floor open; a fountain plays in the centre of the patio, and a broad arcade or piazza all round forms a most agreeable lounging place in hot or wet weather.”

They probably wished they could have just stayed in Tepic. But they had a duty to report their trouble on behalf of the passengers, hoping Mr. Forbes had some power to assist. After hearing their case, Forbes wrote to his superior, the U. S. Minister to Mexico, the Hon. R. P. Letcher, who resided in Mexico City.

The Minister to Mexico

Robert P. Letcher was the former governor of Kentucky and well-connected politically, an intimate of Henry Clay and James Buchanan. He arrived in Mexico City as the U. S. Minister in 1850, a post he would be leaving come August. After reviewing the request from Forbes, he quickly drafted his response on July 17.

Letcher wrote that the Emily’s passengers had a valid lien against the ship. He advised Forbes to enforce the lien in order to procure transportation for the American citizens. If Forbes had to advance any of his own money, Letcher was certain Congress would quickly appropriate funds to reimburse him.

“I expect a just Congress representing a liberal and magnanimous people would never consent to allow a Consul who had kindly furnished funds to prevent American citizens from starving in a foreign country to go unrewarded…

“My ardent desire is that these unfortunate American citizens shall be particularly and especially cared for and I am well satisfied that I do not miscalculate in expressing the opinion that you will do every and all things to render their situation as comfortable as possible under the existing circumstances,” he concluded.

A Saving Grace?

When the Archibald Gracie, an American barque, arrived in San Blas at the end of June, Captain Peters agreed to take the Americans to San Francisco for $6,000. Capt. Harvey refused to make a deal, though. Forbes, echoing the advice of Letcher, which he received too late to be of use, put on some pressure.

“The Counsel told our captain that he must come to terms or he would take his Ship and Cargo and send us on he said that he would Advanse $5500 and pay up the [debt] at San Blass and put a man abord with him and he might go and sell his Coal our Captain told us if we would raise $500 he would Charter the bark we…agreed to do it On July the 17th the Archible Gracia of Boston was Charterd to take us up to San-francisco for $6000 $500 of whitch we paid ourselfes.”

It would take another 11 days before the American ship was ready to sail, though. By then, the Ransoms and others had endured their involuntary shore leave for seven long weeks. Two more men died in San Blas, including “Old Antiny,” the slave.

The Archibald Gracie sailed on July 28, heading northwest to San Francisco via Hawaii, according to William Ransom. At last! They were free from Mexican soil and back on their way to California. If the men thought things were about to improve, they were sadly mistaken. Captain Peters, continuing in the mercenary tradition of his ilk, used little of the charter fee to supply the ship with provisions for his hostage passengers.

Once again, the travelers were reduced to starvation rations, even worse than they’d endured previously. “After we had been out 10 day we wer redused too 3 pints of water and ½ pound of bread…On the 28th of Aug we redused to 1 pint of water and no bread at all All that we had to eat was ½ pound of fresh pork and 6 ounses of flower…water sold for 200 [two dollars], per pint.“

The harsh voyage lasted 44 days and 18 more men died, as the others were reduced to skeletons. Starvation induces a state of mania in its early stages, but as the body consumes itself in an effort to keep vital organs functioning, lethargy sets in. There was little activity on board the Archibald Gracie as she closed in on the California coast.

The men spent each day haunted by the twin demons of boredom and hunger. Having little to do, their minds ruminated on their favorite foods and beverages, wondering if they would survive to partake in them once more.

The Indiana group lost another man on August 21. Hazelette Lanning, one of the Ransom’s neighbors, just 23, received last rites. Only the fact that his mother died in 1850 spared her from bearing the loss of her son. Three other men died the same day. Two of them, partners from Vermont, died within five minutes of each other. “[T]hey were put on 2 planks and side by side and the shi[p] Hove to and burried both at once I tell you it was a dradful sight.”

California At Last

The long-suffering Argonauts finally arrived in San Francisco on September 10, 1852. The ordeal nearly over, those passengers with the strength to stand gazed with relief at their destination as they passed through the Golden Gate and approached the pier. At least a dozen men from the Emily were still so prostrate from malnutrition that the local police chief arranged to have them carried to the State Marine Hospital for care.

“The People here says that there wan no pasingers ever came in here in so bad a condition.” Indeed, the fate of the Emily passengers became notorious.1 What wretched remains of humanity came stumbling down the gang planks from the Archibald Gracie! The people of San Francisco were used to such pathetic sights, but this had to be one of the worst.

Over seven months had passed since the Ransoms had left home, more than six of those just to cover the distance from Panama to San Francisco. The brothers made their shaky way off the ship and left the wharf, ready to start a new adventure, once they’d found some decent food and recuperated from their travels. But first, they needed to send a letter home to let everyone know they were still among the living.

George Blanchard’s sentiments were undoubtedly echoed in a hundred other letters heading east: “Dearest Parents It is with pleasure that I have after a passage of seven months and passed through so many troubles and trials at last an opportunity to write to you and let you know that I am alive and well as you know doubt think me dead.”

[Updated August 17, 2021]

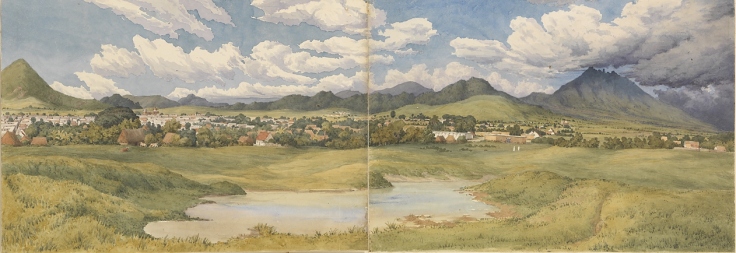

Feature image: View of San Francisco in 1850. Painting by George Henry Burgess. (Wikimedia Commons).

Sources:

Archive material

- David T. Gillis Diary, 1852-1854. Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific (link to my transcription).

- George B. Blanchard, Letter to his Parents. Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Henry Zane Jenkins correspondence, 1851-1853. HM 16791-16808. The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

- James Chelton, Letter to His Brother and Sister. Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Mexico and United States Border Microfilm Collection, San Blas, MX – Mexican Consular Dispatches 1837-1892, Microfilm 0550.71. Arizona Historical Society, Tucson.

Books

- Delgado, James P. 1996. To California by Sea: A Maritime History of the California Gold Rush. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC, pp. 47-74.

- FitzRoy, Robert. 1853 “Further Considerations on the Great Isthmus of Central America.” The Journal of the Royal Geographic Society, Vol. 23. Dr. Norton Shaw, ed. John Murray, London, pp. 171-190.

- Lewis, Oscar. 1949. Sea Routes to the Gold Fields. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York.

- Mayo, John. 2006. Commerce and Contraband on Mexico’s West Coast in the Era of Barron, Forbes & Co., 1821-1859. Peter Lang, New York.

- Portrait and Biographical Record of Kalamazoo, Allegen, and Van Buren Counties, Michigan, Containing Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens…1892. Chapman Bros., Chicago, pp. 802-3.

- Rasmussen, Louis J. San Francisco Ship Passenger Lists, Vol. IV. pp. 62, 63, 83, 110, 113-115, 121, 122.

Newspapers

- Daily Alta California

- Sacramento Daily Union

- Weekly Alta California

Websites

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Blas,_Nayarit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_P._Letcher#As_a_diplomat_to_Mexico

- When a British barque named Emily arrived in San Francisco a week after the Archibald Gracie, the Daily Alta California insinuated (but did not explicitly say) that this was the notorious ship with 17 deaths that had stranded her passengers in San Blas. It was not that ship. Registered in Hull, this ship sailed from Liverpool in September 1851 under command of Charles Clinch, who died en route and was replaced by Chief Mate Charles Richard Lygo. Her cargo consisted of quicksilver bottles, shot, whiskey, wine, rope, and various other trade goods. The British barque Emily that picked up passengers in Panama in March 1852 was registered in London and left that city in April 1851 on course for Sydney. She was erroneously reported lost in heavy storms off Madras, India, in June. In Sydney, master J. Harvey loaded her hull with coal and sailed to Panama, where Harvey placed an ad in the Panama newspapers to lure passengers. After abandoning those passengers in San Blas, Harvey sailed south to Acapulco where he could sell his coal to the steamships that stopped there regularly for fuel and food. This Emily was reported in that port on August 15 and September 7. It appears that after selling the cargo, Harvey returned to Sydney for another load. He never sailed to San Francisco. ↩

My, what a dramatic episode!

LikeLiked by 2 people

When I first read that the Archibald Gracie had brought the Emily passengers to San Francisco, I thought some kind American captain had come to their rescue. How wrong that idea turned out to be!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The world is full of those that will take hold of any desperate situation and use it to make a buck!

LikeLiked by 3 people

How sadly true, that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That was my thought as well. Despicable behavior.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Seven months is just unimaginable, and considering the horrible conditions, it must have felt like seven years!

LikeLiked by 2 people

One irony is that William Ransom fell in love with sailing. He even built a schooner, named after his son Harvey, that plied the waters of Lake Michigan for many years.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yikes, but good for him I guess. But yikes, lol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s hard to imagine! I would never have set foot off dry land ever again after that ordeal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

His tale will be coming up in a few weeks. Stay tuned!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really, this is almost too sad to read. I have goosebumps, and I feel so bad for them.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It really is difficult to imagine how truly bad it was. The survivors seem to have just put it behind them and moved on (except the one who died in the hospital).

LikeLiked by 2 people

They had no choice. But you have to wonder if they had PTSD and it took a toll in a hidden way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

They probably all gained a hundred pounds. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I sure would have!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a horrendous experience! They were lucky to survive. Mr Letcher looks as though he never had to survive in starvation rations …

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL. I’m betting the same goes for William Forbes.

LikeLike

More than likely I would say!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You do tell a marvelous tale.

I’m still processing the story and what it has to say about how we treat one another…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Maggie! There was no shortage of bad actors in the westward movement. Some theorize that the absence of women and social structures (churches, schools, families, etc) had a lot to do with it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

History is fascinating – and more so (to me) with a family connection.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s as good of ending to this story as you can expect I guess, but what a struggle these men went through to get to California. I cannot imagine the horror of it. Fascinating, though.

LikeLiked by 2 people

They didn’t have cushy lives to begin with, so it wasn’t quite as horrifying to them as it seems to us, I think.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good point. Perspective.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m amazed anyone survived that hellish-sounding adventure!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Kinda like being a POW, really, except without the hard labor and beatings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How utterly dreadful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That actually seems like an understatement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For sure!

LikeLiked by 1 person