By Eilene Lyon

In America we tend to think of sauerkraut as a traditional German dish. It was also an important food to my 3rd great-grandparents in the Jenkins-Bedford line. Their heritage was Welsh-English, not German. Abigail (Bedford) Jenkins mentions it twice in her gold-rush letters to her husband, Henry Z. Jenkins.

From August 1851: “our cabbage are heading nicely we hope thee will be here to eat craut…”

From June 1852: “we have all from the little run to the orchard planted with truck we had thought thee would certainly be home to eat saurcraut this season with us but I suppose we will be disappointed in that…”

Clearly they did not make the “craut” for purely health reasons or simply to preserve the cabbage—it was a tasty treat! Pork was a protein mainstay in their diet. These two staples went together like, well, pork-and-sauerkraut.

Sauerkraut, or fermented cabbage, is not a European invention at all. There’s evidence for it in Mesopotamia dating back perhaps five thousand years. Allegedly, Genghis Kahn brought it from Mongolia to eastern Europe in the 12th century.1 Koreans have their own preparation known as kimchi, but aside from seasonings and fermentation method, it is essentially the same thing as sauerkraut.

While this preserved cabbage helped sailors prevent scurvy on long sea voyages, the vitamin C we may get from traditionally made sauerkraut is hardly necessary to our diet. We get plenty of ascorbic acid from modern foods without even trying.

Perhaps you’d enjoy a bit of a scientific explanation for what happens when you combine shredded cabbage and salt in a crock and store it for several weeks. Salt breaks down the cell walls in a way our digestive system can’t. This cellular rupture allows us to absorb the nutrients found in the cruciferous vegetable, and it “releases isothiocyanate, or mustard oil…This oil adds subtle flavors and aromas.”

Salt prevents the growth of microorganisms that could spoil the food, making it either toxic or unpalatable (slimy). It does not harm some good bacteria found in the cabbage, “namely the lacto-fermentive critters Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactobacillus brevis, and Lactobacillus plantarum.” Yum. From these we get the lactic acid that contributes to the good taste of the finished product.2 Undesirable is acetic acid (vinegar).

A recent study, concerned with the preparation of fermented foods in retail and food service establishments, tested the effects of the process on introduced E. coli and Listeria pathogens. As fermentation reduced the pH well into the acidic range, both potentially lethal organisms died off. After nine days they had effectively disappeared entirely. So, if you’re buying kraut or kimchi at your local health food store, you just need to be sure it’s at least that old to be on the safe side.3

If you’d like to try making your own sauerkraut, there are modern recipes available (including in the “Germs Preserve Us” article cited, which is a great read, BTW). Here are a couple I found from the early 20th century that might be much as my ancestors prepared it. They contradict one another in a particular detail: one says don’t pound it, the other recommends vigorous pounding.

Recipe 1

“In answer to Mrs. J. N’s. request for sauerkraut recipe the following one is very good and makes a kraut that stays white and will keep until the last of it is used up. There will be no trouble with mouldy [sic] or spoiled kraut on top.

“Use a stone crock or oak keg. Shred the cabbage fine and long with a kraut cutter. Use one tablespoon salt for each gallon of cabbage, no more. Mix salt thoroughly with cabbage before putting into keg. I mix a gallon at a time. Use hands or wooden spoon, never metal. Press in keg until solid, but do not pound as this bruises cabbage and makes it dark. Set in a cool place and if not enough brine to cover pour on water until it is all covered, adding each day as needed. Be sure to keep plenty of water over the top of cabbage and weight it down. If skum [sic] rises on water, skim it off. Boone Co., M. B.”4

Recipe 2

“I enclose a copy just as it was written for us by an old German neighbor many years ago. If any reader doesn’t own a kraut cutter, very good work can be done with a large slaw cutter. A wooden potato masher may be used for a pounder. Be sure to use rock salt.

“Split the cabbage in two and cut out the heart, also cut out coarse parts of ribs if it is very coarse. Adjust your cutter close, according to directions, the second and third knives elevated accordingly. Discard all rough material. A large handful of wheat flour at the bottom of your crock or barrel; a layer of about three inches of cabbage, and after being pounded down well, sprinkle with a small handful of rock salt and a few grains of whole black pepper. Put down the second layer in the same way, and use besides salt a sprinkling of juniper berries; you can get them at any drugstore. Keep this rule up alternately, and pound hard until the water is covering the kraut. Then cover the whole top with clean cabbage leaves. Use a hard wooden cover with a clean heavy stone on top. Once a week the fermenting juice should be skimmed off, wooden cover and stone being washed at the same time and you will have the most delicious sauerkraut. M. D. New York”5

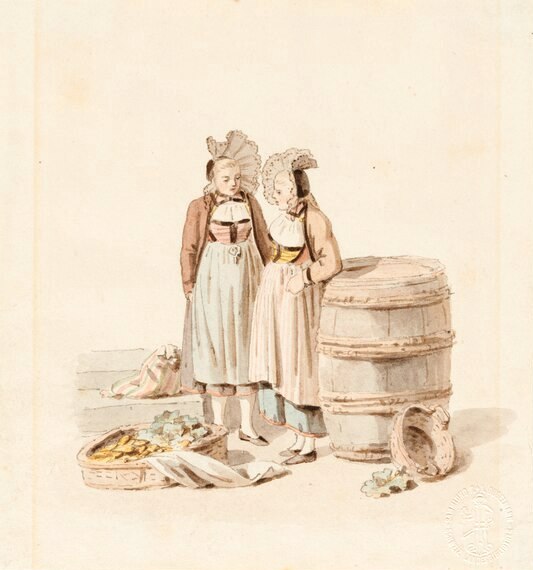

Feature image: Russians preparing cabbage for winter. (Wikimedia Commons)

- James Trager, The Food Book (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1970), p. 24. ↩

- Thomas Greene, “Germs Preserve Us,” Gastronomica 11, no. 3 (2011): 60–67, https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2011.11.3.60. ↩

- Sujan Acharya and Brian A. Nummer, “Retail Risk Assessment and Lethality of Listeria Monocytogenes and E. Coli O157 in Naturally Fermented Sauerkraut,” Journal of Environmental Health 84, no. 5 (2021): 8–13, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27286301. ↩

- “Sauerkraut,” The Nebraska Farmer, October 1, 1921, http://archive.org/details/nebraskafarmer6319unse, pp.11-12. ↩

- The Rural New-Yorker (New York Rural Pub. Co., 1917), http://archive.org/details/ruralnewyorker76, p. 1221. ↩

I have never tried sauerkraut, but I do like coleslaw. How would you describe the difference?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Coleslaw is raw, crunchy, and includes salad dressing. Sauerkraut is much more tender, tangy, and has no dressing. It’s just the cabbage.

LikeLike

I like raw and crunchy, and I make my dressing without mayonnaise—just apple cider vinegar, olive oil, a bit of maple syrup, and salt and pepper.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I consider kraut to be more of a condiment than something you just eat by itself. It’s great on Reuben sandwiches or with all kinds of sausages.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Since I don’t eat meat, that’s probably why I have never had sauerkraut.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That makes sense. It goes well with some veggies, too, such as potatoes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoy cold kraut often with breakfast! I did a blog post about kraut a while back because my grandfather Clabe Wilson made it. His wife Leora wrote that he cut boards to fit into the top of the crocks, weighting the boards with bricks to keep the cabbage under the brine as it began to form. I didn’t find the recipe they used but I bet it was close to your first one. We grew cabbages a few times but I’ve never tried making sauerkraut.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never tried making it, either, but might try it sometime. I’m trying to veer away from commercially processed foods.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can get healthier sauerkraut from health food stores, in the refrigerated section!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I expect it is much better from there.

LikeLike

Yes, refrigerated is fresh, well, it should be. On the shelf variety is down right awful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I need to elevate my taste buds. 👅😋

LikeLiked by 1 person

The difference in taste is huge. Elevate those taste buds, and they’re love you forever😜

LikeLiked by 1 person

Will give it a try!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never knew how sauerkraut was made. Thanks for the info!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Seems like a fairly simple process to me. I might try it sometime.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good sauerkraut is good…bad is awful…

LikeLiked by 1 person

😂😂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Correct 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m surprised at the differences between the two recipes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

They are radically different, aren’t they?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s more to cabbage than I thought! 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Surprise!😁

LikeLike

I enjoy a good helping of sauerkraut especially when we were housesitting in Germany. Now I buy Sum Yum Kimchi as it’s much preferable than the sauerkraut made here. Interesting that non European descendants brought the recipe to America.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like it with sausage and potatoes. Good stuff! I’ve never had kimchi, but should give it a try.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you like chillis you will. Korean flavours. Yummy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do like spicy food.😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t had sauerkraut in ages, but I used to frequent a small indoor mall for many years and there was a German butcher shop there. Every weekend, the butcher shop sold bratwurst on a bun topped with sauerkraut. I’ve never been to Costco, but I know people rave about their hotdog deal, but it has nothing on this butcher shop (now closed). People would line up and down the corridor and even if you weren’t hungry when you got to the mall, you’d have a bratwurst on a bun topped with sauerkraut before you left as the smell was so enticing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do love a good brat with sauerkraut and spicy mustard. That butcher shop would have been a regular for me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tasty stuff for sure – you could not pass it up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wouldn’t!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now I’m craving pork and sauerkraut. It’s on the menu roster!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad I could whet your appetite, sir!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed your post and recipes. My kids love kraut and kimchee. They’ve told me that fermented foods are good for your health. I’ve been eating sourdough bread instead of whole wheat lately because of that. I was going to research today, why. You’ve helped me on the road of discovering why.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You should read the article I pointed out. He has some interesting things to say about health benefits of foods.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will! Thanks for pointing it out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

👍🏼

LikeLiked by 1 person