Black History Month

By Eilene Lyon

Genealogists and historians rely on many different record sets in their research. Often, we focus on the variable information on a form, items that identify our ancestors and relatives: name, birth date, address, occupation, physical description. It’s also important to learn about the record source itself.

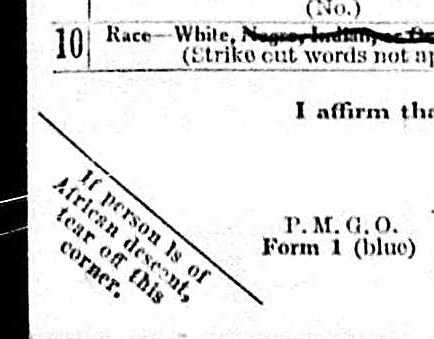

The World War I draft forms provide a wealth of such vital statistics. When I was looking at the draft form for my great-uncle Benjamin Alton Crandall, something else caught my eye. Something printed on the form itself, down in the lower left corner:

There were three draft cycles during the war and different forms printed for each. The first two cycles had these tear-off corners. The third just had boxes to check for race. In sum, 24 million American men registered for the WWI draft.

With a stack of completed forms in hand, a draft board employee could quickly flip through and pull out the ones belonging to Blacks. Not to recruit them, but the opposite. This was a continuation of discrimination as usual. At the beginning of the war, the quota for Black enlistees was quickly filled and they were turned away from recruitment centers.

Blacks have served in every armed conflict in this nation’s history, from the Revolutionary War onward. In the military, they were relegated to segregated regiments led by white officers.

After the Civil War, Black troops were consolidated into two infantry regiments—the 24th and 25th—and two cavalry regiments—the 9th and 10th. They were collectively known as Buffalo Soldiers (there are many speculations as to how the name came about), and were primarily deployed in the West and Southwest. There, they were often engaged in the Indian Wars.

In the early 20th century, at the height of the Jim Crow era, Blacks saw military service as a way to earn respect in their communities. Out West, the Buffalo Soldiers were generally well regarded, even treated as heroes, in the communities they served. Unfortunately the South, in particular, did not want them to sign up. Planters did not want their primary labor source heading off to Europe, for one thing.

That began to change as casualties mounted and the French were desperate for troops to combat the Germans. Draft boards (comprised of all white men) soon began accepting more registrations from Blacks.

Blacks were inducted separately, segregated during training, sometimes not given a change of clothing, and forced to sleep in tents instead of barracks. Then they wound up in labor battalions, rather than assigned to combat. This caused enough agitation among Black recruits that the Army eventually relented and formed two combat divisions, the 92nd and 93rd.

During the course of the war, 2.8 million American men served and about 380,000 of them were Black. Though Blacks were about 10% of the population, they made up 13.5% of those who served. Those in labor battalions worked extraordinarily long hours: unloading ships, transporting equipment, and serving in menial positions such as janitors. Despite the necessary and difficult work they performed, they were treated poorly.

By war’s end, Black troops served in just about every role and unit type, though very few were admitted into the commissioned officer ranks, usually only as high as First Lieutenant. The two combat divisions had very different experiences. Some were forced into doing labor, such as building railroads, instead of serving on the front.

The 92nd division suffered from racism at the top of the chain of command, and as a consequence did not receive adequate training or integration with companies already on the battlefield. The 93rd division (four regiments) received orders to integrate with the French troops, who generally treated them as equals.

One regiment in particular, the 369th, comprised primarily of men from the North, many from National Guard units, distinguished themselves on the battlefield. This regiment went by several nicknames, the best known being the “Harlem Hellfighters.”

This entire unit received France’s highest military honor, the Croix de Guerre, and many received individual commendations for valor. The other three regiments in the 93rd division also received high honors.

Unfortunately, when the Black soldiers returned home with high hopes of receiving respect in their home communities, they were soon disillusioned. Though the 369th did have a New York City parade in their honor and accolades, most were subjected to the same discrimination and violence they had left behind when they went to Europe.

Black troops were not fully integrated into the American armed services until the Korean War.

Feature image: Members of the “Harlem Hellfighters” from New York, in France during WWI (National Archives)

Sources:

https://armyhistory.org/fighting-for-respect-african-american-soldiers-in-wwi/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_history_of_African_Americans

https://www.uso.org/stories/2125-black-world-war-i-troops-fought-to-fight-for-their-country

https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_World_War_I_Draft_Records

An informative post for Black History Month, combining genealogical searches with the harsh realities of the treatment of African Americans who served in the Forces throughout history. Thanks, Eilene.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, I have never noticed that on the many WWI draft registrations I’ve looked at—now I will go back and look. And thanks for uncovering yet another ugly chapter in our country’s history of racial discrimination. Just shameful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An important piece of history for us all to learn…systemic discrimination is so ugly, and if we think it no longer exists, we’re all sadly mistaken. Thank you for bringing this to light.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, I’m afraid it is still a part of everyday life, all around the world. We seem programmed into an us/them mentality.

LikeLike

An excellent share, Eilene. The respect they deserved they got from the French. Quelle surprise – not.

It’s another ugly chapter in the story of Blacks in the States.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Very much so – all you said.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s exactly the comment I was going to make, Dale. And on and on it goes . . .

LikeLiked by 2 people

😊 That’s ‘coz like-minded and smart people hang out in the same groups 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

I can go with that! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

An interesting post Eilene and so incredibly sad. Unfortunately, so much discrimination is still happening. Here there was a whole generation in some areas of NZ where Maori men were killed in the first and second wars. Like that saying goes “history repeats” and one day us humans might learn that it’s not ok to discriminate on race, religion etc. Time for my early morning walk.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Will we ever learn? Somehow I think we will have to evolve as a species – not in our lifetimes, in other words.

LikeLiked by 2 people

After the Emancipation Proclamation African-Americans served in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. They served in segregated regiments in the United States Colored Troops (USCT). White men were officers in the USCT but generally the highest rank a Black man could attain was sergeant. USCT troops were largely relegated to doing menial labor and guard duty. Men from free states and Confederate states enlisted on their own, but in the border states, slaveholders were allowed to enlist their slaves and were paid the bounty that would have been paid to the soldier. The pay was also lower than it was for whites. Later, when pensions were approved for Civil War military service, the government made it more difficult for Black men to qualify for a pension.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The indignities heaped on these men was legion. Thanks for sharing all that detail, which was beyond the scope here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is so fascinating and sad with the tear off corner on the paper work. A bit of history of our Palm Springs home we discovered in the paperwork when we purchased it. It stated that Negros were not allowed to use the front door or stay overnight. We bought the house in 1992, it was built in 1937. Of course, current law at that time got rid of that discriminatory language.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Redlining and restrictive covenants were used extensively until passage of Civil Rights Acts in the 1960s. It took even longer to get rid of it, and people still do it illegally.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unbelievable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shocking, but not surprising. I knew, for example, that black and white US soldiers were segregated over here in WW2 and the locals expected to go along with it (which a lot didn’t, to their credit). But in terms of general prejudice, i don’t think this country was much better even if we didn’t have actual segregation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The French were much more accepting. It may have been because of their colonial intrusions in Africa, Caribbean and South America. Apparently they brought in a lot of Senegalese to serve in the war. Hitler actually spread propaganda to try to turn the Black troops against the U.S. by emphasizing how badly they’d been treated at home.

LikeLike

That would be almost funny if it wasn’t so grotesque.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah. Not really funny.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would seem incompatible, this idea of “one nation under God” and the piss poor treatment accorded generations and generations of men who simply wanted to do their part.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh goodness, don’t get me started on that track! Burning crosses on lawns……

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post. I am reminded of how disappointed many African Americans in the Mass. 54th and 55th were with their labor details—it was distressing for them not to be assigned to true military missions, and their unequal payment didn’t help!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for stopping by, Donna! I’ve been interested in Blacks in the military since I ran across one who was hired as a cook by company officers in the Mexican War and they wound up enlisting him in the company (all white) while in Mexico City. Then I learned that there were integrated companies in both the Revolution and the War of 1812. Who knew? But yeah, being consigned to all the drudgery and none of the (possible) glory must have seemed a raw deal.

LikeLiked by 1 person