I still feel the sentiments expressed here. I often wonder just how far off I am when I write about people from earlier centuries, people I never knew. Originally published January 15, 2018. EL

By Eilene Lyon

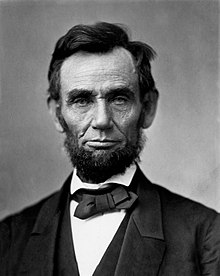

We recently watched The Abolitionists, by American Experience. It is an excellent and high-production-value 3-part series about the role played by the anti-slavery movement in the lead-up to the Civil War. One thing that struck me was the portrayal of Abraham Lincoln in the film. I’ve read books and articles on Lincoln, seen documentaries, even gone to Ford’s Theater, but the angle taken in The Abolitionists was new to me. For a real eye-opener, I went to Newspapers.com and read some 1863 articles from South Carolina about Lincoln. (If you’re game, click on the links below this story)

If you’ve read the novel, The Good Lord Bird by James McBride, you’ll find the characterizations of John Brown and Frederick Douglass in this program a bit varnished, by comparison. But fiction has the advantage of playing with personality. Writing non-fiction portrayals is more constrained.

Imagine writing a biography of someone you know very well: a parent, a sibling, your BFF. You need to convey the events that shaped them, and attempt to explain why they have done the things they’ve done in life. You would want to describe their physical traits, mannerisms, personality quirks, etc. When you finish and ask the subject to read it, do you think they would feel you’ve captured their true essence?

It’s not easy, is it? (I sympathize with anyone who’s ever been interviewed for a newspaper or magazine article. It can be torture to read the result.)

Take that same task and apply it to someone who’s been dead a long time, someone you’ve never met. The world he or she lived in was entirely different from your own experience. No matter how much personal material you have on hand in the form of photos, letters or journals, you can never really figure out what made them tick. Every characterization will fall short or wide of the mark. Someone else working with the same material will infuse their own biases and come to different conclusions. Sadly, there is no such thing as “true” history.

This is why I sometimes fear to express my interpretations about the ancestors, and others long gone, whom I write about. Am I being fair to them? Does it matter? What do you think?

This is something I often struggle with—both in writing my blog and even more so in writing my family history novels. In both efforts I am writing about people I never knew (or barely knew) and am relying on records, newspaper stories, maybe a family recollection, but little else. On the blog I tend to keep to the “facts” because I am not writing fiction or creating characters. But in my books I am creating characters to tell the stories and then I know I am taking liberties. But that’s why I take special care to describe them as fiction inspired by a skeleton of facts.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I appreciate your care in presenting the information you have. I do my best to keep to verifiable information or at least a first-hand account. But I am also aware I can creep toward embellishment at times for the sake of story. Perhaps I come close to reality, but then maybe I’m off the mark. Unfortunately there is no way to know.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And we all do the best we can. That’s all we can do. At least we are honoring the lives of those who came before us.

LikeLiked by 3 people

And if new evidence comes to light, I don’t dig in my heels. We must always be open to revision.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Absolutely! I always update and correct my posts if I find new information—even when it reveals I made a stupid mistake!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Especially important on a blog. I long ago gave up trying to get people to correct Ancestry. A few exceptions, such as when my grandparents were attached to incorrect children.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Can we ever really know for sure regarding another’s story- no. Can we even trust our own memories when trying to write our own stories- that’s questionable as well. You are someone who would not compromise the facts you feel correct about Eilene. You also do not embellish or sensationalize. You present in a way that allows readers to think and ponder as we all do regarding history anyway. I think a reader is naive if they believe that historical “facts” are 100% correct.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I try not to wander far from the facts. Stephen Ambrose said, “Don’t write anything you can’t prove.” That is probably an impossible standard. What I strive for is “don’t write anything you can’t support with evidence.” And yes, any presentation of history is likely to contain errors. Evidence conflicts and historians must make decisions.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know exactly how you feel. For the most part I tend to stick to “just the facts, ma’am” in my posts as I don’t feel comfortable speaking in my ancestors’ voices, as some family history writers do (and some instructors ask us to do). I know for myself, people would still get things wrong as I’m fully aware there’s so much more going on inside my head than even those closest to me don’t see. It’s not generally bad stuff, but I think we’re all similar that way. I’d hate to see someone in the future try to ascribe motives to my behaviour with no real understanding of who I was beyond the basic details of my life and maybe even some samples of my writing (correspondence, fiction, reviews, blog posts, essays etc.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

As long as I have supporting evidence, I am comfortable with entertaining ideas about how it might have been (with caveats). I think some honest speculation can enrich a story and invite people to read and think about a situation on a deeper level.

As for a future biographer writing about me, they certainly won’t get it “right,” but if they use good source material (including private writing) I certainly wouldn’t fault them for it. After all, if someone found me worthy of writing about, I’d be flattered. This is all assuming I’m dead, of course.😏

LikeLiked by 1 person

People and this includes writers and news agencies are all about sensationalism – it sells. I was working on (never finished) a family history. While researching, I found information that in today’s light would be offensive. As the 1600s, 1700s, 1800s were all different times with different norms my approach was simple, present the facts, pass no judgements. The individuals involve cannot explain themselves, and who knows if the facts I found are complete or even correct.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That’s much the approach I prefer to take. No editorializing. This is what we believe happened based on this evidence. Am I 100% successful? Probably not. I do try hard, though, and stay open to correction.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That is all you can do, anything more or less is a disservice to the ancestor.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Danny.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Take that same task and apply it to someone who’s been dead a long time, someone you’ve never met.

And therein was the crux of my difficulties while sorting through all the family photos and letters and documents this summer. I’d not met many of the people in the photos, and without knowing about their particular circumstances, their stories, I didn’t know what to make of some of the photos. Did what I keep reflect who they really were? Or was it me superimposing who I want to think they were onto them?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Isn’t being remembered (hopefully in a somewhat accurate way) better than being forgotten entirely? I say it is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

From reading your book and your posts, I believe you are inherently honest and stick to facts.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I do try. Thanks, E.A.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The qualms you’ve expressed in this post is the reason I write fiction. I wouldn’t want to ascribe motives and characterizations that I would have no way to verify. When I wrote about my grandmother’s early life a few years ago, I cited supporting evidence for everything I said.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds like many family historians take the fiction approach. I’m reading an excellent novel based on a real person right now. Like you, I absolutely believe in source citations otherwise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eileen, to me it is apparent from the wealth of references citing where the information was gleaned for each of your posts, you should have no worries about writing information that is incorrect and certainly not potentially libelous. It is clear how much research and effort goes into each one of your posts, even the small “Bio Bites”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Linda. I think is is possible to present facts in a lively way with good writing and remain faithful to source material. But as you point out, citing my sources is a big part of that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You do just that Eilene.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a difficult question but I will say this. I have come to assume there’s a bit of fiction to any narrative about the past. With all the facts in the world, we don’t always know context of an event or a person’s words. That’s how we get so many new books and documentaries that all assess a story differently.

Fresh eyes bring new perspectives that can be interpreted into biases or presented with an absolute faithfulness to the facts.

I’m always impressed with how you build a body of evidence and then either draw what feels like a fair or sometimes obvious conclusion. You often question how it must have felt or what it must have been like, leaving the reader with food for thought but no varnished story that may be unfair or untrue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brandi, what you say seems to be a consensus among people who read nonfiction. There is always a slant or bias that can be taken as fiction. Or sometimes just creative license. In my book, someone pointed out that I said Abby paused to dip her pen and consider what she would write next in her letter. I know she used pen and ink and because paper was very expensive, she would have carefully considered her words before putting them down. Fiction? I suppose so. But I think it creates a living scene that is more than plausible. Nonfiction writers also use what we call hedges: maybe, perhaps, could have been, might, in all likelihood, etc. This indicates we are speculating and is considered legitimate in historic narrative (not academic) nonfiction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such food for thought! I really enjoyed this story and how thought provoking it is!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Brandi. I think I have another in a similar vein in a couple weeks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will look forward to it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would think the sticky part of the label would be in attempting to remain objective about a person. Their opinions and accomplishments happened with a context we really can’t relate to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No doubt it takes some effort and achieving true objectivity, impossible. What we consider difficult and hardship, they thought of as everyday normal circumstances.

LikeLiked by 1 person